Traditionally in Punjabi culture, when a daughter was born, the women in the family would immediately begin creating decadent phulkaris that would one day be used in her wedding celebrations. As an important component of a girl’s material wealth, the unembroidered cloth was a canvas for Punjabi women’s feelings and inspirations. Punjabi girls were taught how to embroider by their mothers at a young age and would eventually teach their own daughters the same skills, passing down a tradition of phulkari that has become a major signifier of Punjabi culture.

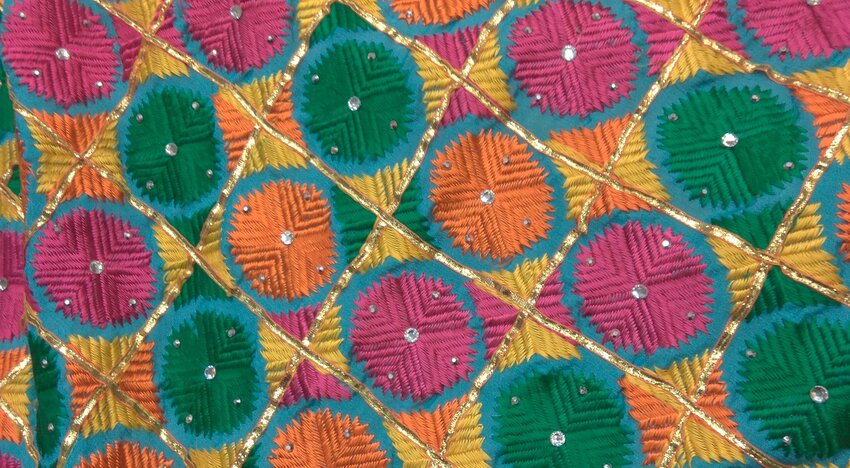

Phulkari, literally meaning “flower work,” is a vibrant and intricate textile that has survived in East and West Punjab since the 15th century. Before mass commercialization and modernization caused phulkaris to become available across the world, Punjabi women would gather on cots outside, singing folk songs and hand-embroidering unique phulkari pieces to be used as head coverings, bedding fabric, or wall decor. Traditional designs took inspiration from family and rural life, making each phulkari a personal and distinct artistic creation. While the textile is rarely hand-embroidered today, the designs Punjabi women created have survived colonialism, political revolutions, and displacement, making what once was a leisure activity, a symbol of the severed Punjabi identity.

How It's Made

Unlike modern phulkaris, phulkaris from the pre-modern era were made by spinning cotton into yarn on charkhas (spinning wheels), which were operated by Punjabi women. The yarn was then dyed and hand-woven into a khaddar, creating a tough and coarse base for embroidery. The untwisted silk floss for embroidering, called pat, was sourced from Kashmir, Bengal, Afghanistan, and Turkistan and was dyed locally in Amritsar and Hammu.

The process of embroidering was delicate and highly imaginative; since Punjabi women did not use stencils, each thread of the khaddar had to be meticulously counted before beginning. To embroider the cloth, pat was sewn gently from the opposite side of the fabric typically in vertical, horizontal, or diagonal darn stitches. Various colors, shades, and stitches added complexity and vibrancy to each design.

The History Behind Phulkari

Traditionally, phulkari work was a social, leisurely activity and thus, was never intended for commercial sale. The arrival of the British, however, created a market for phulkari pieces overseas. Phulkari designs were modified for European tastes and displayed at many European and North American International Exhibitions, spreading the textile across the world.

However, in Punjab, by the 1920s, phulkaris began going out of fashion with women stitching and wearing phulkaris less frequently. The Partition of 1947 divided the Punjab province in half — with western Punjab in modern day Pakistan and eastern Punjab in modern day India — resulting in a colossal loss of Punjabi heritage. Phulkari designs and techniques were never documented and were typically passed through word-of-mouth or example from generation to generation. In the wake of this violent reorganization, phulkaris were lost, abandoned, or destroyed as millions of Punjabis shifted across the India-Pakistan border. The neighbors who once made phulkaris together were displaced along with the nomadic merchants who sold the khaddar and pat, destroying the social bonds essential in keeping phulkari alive.

In the 1950s, the Indian government, focused on diversity and the artistry of Indian handlooms, revitalized the textile. Punjabi women refugees now living across India, separated from their families with little financial support, were able to monetize their embroidery skills. To meet modern needs, there was a further push to create household items with phulkari designs, popularizing the use of the textile beyond clothing. Presently, due to new machinery, phulkari work has become less expensive and time-consuming, allowing it to spread both locally and internationally. While the textile has fortunately remained alive, only a few out of an estimated 52 phulkari stitches have survived the course of history.

Types of Designs

The type of pat, khaddar, and motifs displayed in a phulkari reflect what occasion they are used for. For example, bagh phulkaris, also known as “the garden” because the embroidery covers the entire khaddar, are kept for special occasions. Since this type of phulkari needs an extensive amount of pat — and traditionally, required more time to hand embroider — bagh phulkaris were regarded as an indication of wealth. Like sainchis, these phulkaris could include scenes of rural life.

Thirma phulkaris, on the other hand, are more muted and embroidered on un-dyed white khaddar. In the past, these were mainly worn by elder women and widows, but have become less popular in modern culture and cities. Considered a badge of purity, thirma phulkaris use bright pink to deep red pat which are sewn with cluster flower stitches, wide triangles, and the chevron darning stitch.

The most complex and artistic phulkari, sainchi, requires a strong embroidering skillset to create. Usually depicting rural life, Punjabi women used common motifs like flowers, animals, fruits, jewelry, pots, and kitchenware to craft their designs. Because sainchi phulkaris were highly imaginative, they were considered to be reflections of the embroiderer’s feelings. For example, birds emphasized success and beauty; fruits symbolized prosperity and fertility; and peacocks represented marriage. Chope phulkaris were traditionally gifted by the maternal grandmother to the granddaughter and held sentimental value. The khaddar for chope phulkaris were typically bigger than normal, because they were used to wrap and dry the bride after the ritual bath before her wedding. Typically using golden or yellow pat on orange or red khadder, chope phulkaris use the Holbein stitch so the work is visible from the front and back. The borders of chope phulkaris are left unembroidered to represent endless good fortune and unlimited happiness in married life. While the general use of phulkaris in weddings is still popular, the symbolic chope phulkari ritual has become less common.

Where to Buy It

Nowadays, phulkari work is done on clothing, pillow covers, seat cushions, bed covers, curtains, and more. While the textile has become ubiquitous, phulkari remains a Punjabi tradition. Cities in Punjab, particularly Amritsar and Patiala, have bazaars dedicated to a variety of phulkari pieces. Internationally, online stores on Etsy or Amazon sell phulkari work directly from shops and creators in Punjab. To purchase hand-embroidered phulkaris online, I recommend Pink Phulkari or Zarkaashi.

Punjabi culture and tradition is infused into each stitch of a phulkari. After years of Punjabi culture lost to colonialism and political violence, preserving this textile is central to preserving the Punjabi identity. The vivid colors and intricate patterns of the phulkari tell a decades long story of love and resiliency, pioneered by the Punjabi women who gathered on cots outside with their charkhas, khaddar, and pat to create beautiful pieces reflective of their homeland — Punjab.

Main photo by KavyaT/Shutterstock.