It’s a soft evening in Lisbon, the warmth persisting throughout the branches of the Alfama neighborhood's twisting, twig-like streets. Visitors are gathering at restaurants throughout the quarter, their tablecloths and napkins anchored against the occasional breeze by heaping dishes. Sometime between chouriço a bombeiro (flame-grilled sausage) and bacalhau, a performer will make her way between the tables, close her eyes, and open her mouth. The gentle notes of her voice draw every eye and silence every conversation.

Hundreds of years ago, in the same neighborhood and just after the 1755 earthquake and consequent tsunamis that forever altered Lisbon’s landscape, another fadista began to sing. Her voice was the first recognizable monument in Portuguese folk music, in the midst of a period of unrest and strife that permeated the economically and socially marginalized communities who made Alfama their home. From South American, African, and European countries, families brought not only their worries and dreams, but also their music. Maria Severa’s songs rose from this melodic hum, and fado music was officially born.

Fado—pronounced “faa-dow”—means ‘fate,’ and evolved in the same way as many other traditional styles of music across the globe. Generations unfolded their stories, concerns, and desires into oral histories and tunes that persisted for years after them, incorporating the new into the old.

Maria Severa was the first to be given the title of fadista in the 1830s, but her music elevated the forlorn melancholy she experienced in her neighborhood. The lyrics of her often improvised songs are not widely known, but the subjects and sentiments have echoed throughout fado’s history. They would become the recognizable Portuguese saudade, an indescribable mourning that relates feelings of loss for something never to be found again as well as a longing for what never has been but might one day be.

Fado, as its origin suggests, is not a stagnant art form. Even today the style depends not only on the singer but the establishment, region, and training received. When fado reached Coimbra, home to the legendary Portuguese law school—complete with wizard-style black robes—the elite professionals of the city transformed the music once again. Here in the 1840s, just years after fado was popularized, men donned the traditional academic ensemble and performed with practiced professionalism. Rather than the daily and overwhelming woes that were the focus of traditional Lisbon fado, Coimbra fado focused on the literary traditions of the performers from elite families. With more attention paid to lyricism and musical accompaniment, Coimbra’s historic fado tended to focus less on adversity and more on goals and hope.

Fado then found its way onto the vaudeville stage at the turn of the century, gaining popularity with singers who incorporated new rhythms and influences. The Queen of Fado, Amália Rodrigues, brought fado to an international stage with such celebrity that the entire country mourned her passing for three days. And modern fado, with singers like Mariza, Katia Guerreiro, and Antonio Zambujo, put fado on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

No matter who's singing or where you’re listening, this musical style has a pull that’s hard to describe. It’s the magic of saudade, a deep, soulful connection that takes internal drama and transforms it into something beautiful. The singers and musicians are, of course, enormously talented. Even those who can’t understand the words feel the emotion as singers with enormous voice control hover moments from a sob that never comes.

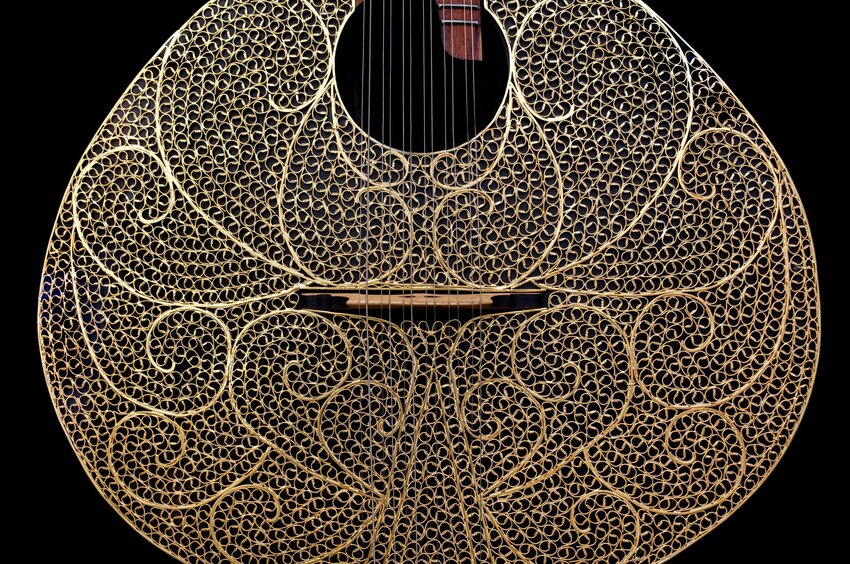

It’s the ultimate cultural dinner-time accompaniment, especially after a long day of scaling one of Lisbon’s many hills. Traditional fado is mostly performed for tourists in Bairro Alto, Mouraria, and Alfama. You’re just as likely to stumble upon live fadistas while wandering, but expect to pay slightly more (or have a minimum spend) for the pleasure of their performance. Just be on the lookout for the tear-drop shaped guitar and signage pointing you to the show.

If you want to know more, make the Fado Museum a stop in your Lisbon itinerary, or get tickets to Real Fado’s performances in some of the most unique hubs across the city. And while there are a ton of places to experience the fado tradition around Lisbon, below are a few particularly great options.

- On Thursdays travelers can head to Parque Eduardo VII to A Nini, a Lisbon tasca (small restaurants that may charge a fee or require you to purchase a full meal) away from the tourist-centered Alfama and Bairro Alto neighborhoods. Run by Nini and her husband, Thursday nights are dedicated to hours of fado performances with musical accompaniment.

- While popular with tourists, Bairro Alto’s nightlife includes several tascas. One of the most crowded (for good reason) is Tasca do Chico, a restored old tavern that hosts fado vadio—nonprofessional fadistas—along with up and coming fado stars on Mondays and Wednesdays.

- Parreirinha de Alfama, not far from the celebrated Fado Museum, is one of the oldest and most celebrated fado houses in Lisbon. Tiles cover the walls and traditional Portuguese dishes litter the tables. Dinner will be a little more expensive for the pleasure of a fado show, but the experience transports every listener back in time and is worth a few extra euros.

- A surviving relic of a pre-earthquake Lisbon, Café Luso offers nightly fado in a historic, domed cellar. This space is intimate, but popular, so book ahead if you’re interested in a slightly elevated experience.